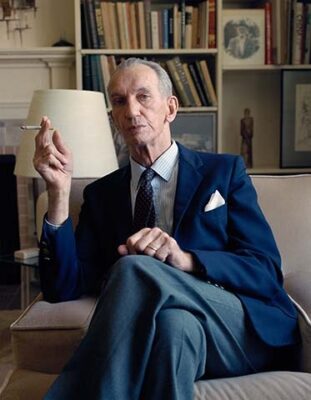

Jan Karski as a young man

There are some people whose experiences during World War II are so fantastical, so filled with drama and danger, that one wonders how they managed to simply keep going. Jan Karski is one such man.

Karski, described by British historian Michael Burleigh as “one of the bravest men of the war,” and whose life was summarized by Elie Wiesel as “a masterpiece of courage, integrity and humanism,” died twenty-one years ago today, age 86.

Born Jan Kozielewski in 1914 in the city of Łódź, in what was then part of the Russian Empire, Karski (an alias he adopted during the war and kept thereafter) was the youngest of eight children from an educated, upper middle class Polish Catholic family. A scholastic standout, he trained in his youth to serve in the diplomatic corps. Like all Poles, he performed mandatory military service, and was a reserve lieutenant in the mounted artillery.

In late August 1939, as Hitler’s agitation over the Danzig Corridor escalated, Karski’s unit was mobilized and ordered to a military installation in Oświęcim on the Polish-German border. Oświęcim is better known by the name the Germans later gave it: Auschwitz, the very symbol of the Holocaust.

The Poles were quite confident they could handle the Germans. “England and France are not needed this time. We can finish this alone,” Karski’s commanding officer confided. In fact, they had no answer for Germany’s blitzkrieg tactics. Within hours on September 1, Karski’s unit was overwhelmed, leading to a long, disorganized and demoralized retreat. The retreat lasted for weeks, until Karski reached Tarnopol. There he and his comrades surrendered—to the invading Russians, who previously agreed to partition Poland pursuant to a secret protocol with Germany.

Karski, who hadn’t even fired a single shot in anger, soon found himself on a cattle car headed to a Soviet POW camp in what is now Ukraine. The camp was highly stratified, but not in the way one might expect. It was the common soldier who had the best accommodations (such as they were), and the officers, considered by the Soviets to be the oppressors of the proletariat, who had the worst housing and the hardest tasks.

Looking to escape, but resigned to the fact that any escape under the circumstances was well nigh impossible, Karski was thrilled to learn of a proposed prisoner swap with the Germans. Polish POWs in German custody would be exchanged for Poles held in Soviet custody of Germanic descent and Poles born in the territories now incorporated into the Reich. There was only one catch: the Russians were only willing to exchange Polish soldiers of the rank of private—no officers need apply.

Karski convinced a Polish private with no desire to participate in the exchange to switch uniforms with him (the Russians weren’t paying particularly close attention anyway). Karski’s decision was prescient. The world would later learn that shortly after the swap, Polish officers remaining in Soviet custody were segregated. Stalin, desirous of eliminating any possible future source of resistance among the intelligentsia and officer corps, personally ordered the slaughter of 22,000 Polish officers and government officials in the Katyn Forest in April and May 1940.

Once the POW swap was effected, Karski found himself out of the frying pan, but now in the proverbial fire. The Germans promised their captives “work” and “food” but it was all a ruse, Karski suspected, and he wasn’t about to give the Germans a chance to prove him right. En route to Germany, Karski jumped from a moving train at night, notwithstanding guards posted on the train with machine guns.

World War II was not even three months old and Karski had effected not one but two daring escapes. His sole focus: to join the Underground and continue the fight for Poland’s freedom. His goal was Warsaw, and the first stop on his trek was the city of Kielce. [About this same time Tom Buergenthal and his parents were living as refugees in the part of Kielce which would shortly become the Kielce Ghetto.]

In a memoir Karski published in 1944, Story of the Secret State, Karski details his life in the Polish resistance. It was a choice fraught with danger. Perhaps no country, with the possible exception of Russia, suffered so much at the hands of its German occupiers. The country simply ceased to exist as a sovereign state—part absorbed into Germany, part absorbed into Russia, and the rest—the Generalgouvernement—treated as occupied territory. Karski is at pains throughout his memoir to explain that there was no Quisling, no serious collaboration with the Nazis on any level at any time.

Karski’s memoir graphically depicts the incredibly dangerous life of a resistance fighter. In Chapter 5 he describes how his close friend Dziepatowski initiated him into the Underground. Dziepatowski’s fate: “[H]e was caught and subjected to appalling tortures, but did not reveal a single secret. Finally he was executed.” Three chapters later Karski meets with Marian Borzeçki (called Borecki in the memoir), a former high ranking government official. His fate: “Toward the end of February, 1940, Borecki was caught by the Gestapo. . . . He was dragged off to jail and submitted to the most atrocious Nazi tortures. He was beaten for days on end. Nearly every bone in his body was systematically and scientifically broken. . . . In the end he was shot.” Karski describes in detail the elaborate mechanisms the Underground employed to prevent a betrayal or arrest from jeopardizing the larger operation. “Liaison women” had the task of connecting one Underground member with another; since members were constantly adopting new identities and new domiciles, only the appropriate liaison woman knew how to reach the appropriate person and arrange a meeting. Karski observes: “The average ‘life’ of a liaison woman did not exceed a few months.”

Even for those who had no involvement with the Underground, life in occupied Poland was one of privation. The diet of those who fared worst consisted “exclusively of black bread mixed with sawdust. A plate of cereal a day was considered a luxury.” During all of 1942, Karski never once tasted butter or sugar.

Karski’s own brush with the Gestapo wasn’t long in coming. Because of his language skills, extensive travels across Europe and retentive memory, Karski was chosen to be a courier—carrying vital information (in his head) from the Underground’s various factions to the Polish government-in-exile in France.

Karski’s first courier mission, over the Tatra Mountains into Slovakia with the help of an experienced mountain guide, then to Hungary, Yugoslavia, Italy and France, went without a hitch.

A subsequent courier trip was less successful. Unbeknownst to Karski on this mission, a previous mountain guide had fallen into the hands of the Gestapo, and told everything he knew—the routes used, the safe houses along the way, etc. It was only a matter of time before Karski fell into a trap. Captured, along with his guide, in Slovakia, he was quickly subjected to harsh interrogations. Fearing, after one particularly brutal session that resulted in four lost teeth and several broken ribs, that he would be unable to hold in his secrets much longer, Karski decided to kill himself with a razor he had surreptitiously stolen from the washroom.

Waiting until the watchman completed his rounds, Karski slashed both his wrists. (I have previously written about incredible courage it takes to end one’s life just to protect the lives of others here). As the blood poured out of his arms,

“I thought of my mother. My childhood, my career, my hopes. I felt a bottomless sorrow that I had to die a wretched, inglorious death, like a crushed insect, miserable and anonymous. Neither my family nor my friends would ever learn what had happened to me and where my body would lie. I had assumed so many aliases that even if the Nazis wished to inform anyone of my death they probably could not track down my real identity.”

Ironically, it was the very act of trying to kill himself that ultimately saved his life. Remaining in the Gestapo prison—with or without revealing any of the secrets he held—would have undoubtedly ended with his execution. Instead, the night watchman heard his groans, and Karski was rushed to a nearby hospital. There sympathetic Slovakian doctors and nurses protected him. Later he was inexplicably transferred to another hospital just over the border, in Poland. (Karski speculates that he was brought there to give away the Underground in the vicinity.)

Once in Poland, word of Karski’s predicament was communicated to the local Underground. With a well-placed bribe to the hospital guard, Karski was able to make good an escape into the arms of the local resistance fighters. Responding to his gushing expressions of gratitude, his saviors were a bit more business-like: “Don’t be too grateful to us. We had two orders about you. The first was to do everything in our power to help you escape. The second was to shoot you if we failed.”

Karski’s tale, while remarkable, is hardly unique. Millions of such escapes, captures, and tortures occurred throughout occupied Europe during the war. What makes the story special for me, however, is first, the fact that Jan Karski was my professor as an undergraduate at Georgetown University, and second, that I never knew anything about his incredible experiences while I was his student. In fact, it was not until his death in 2000 that I learned for the first time in an alumni magazine about Karski’s earlier life. I wondered: had I been so obtuse that I missed any references—direct or oblique—to these matters during his classes? Was I really that clueless at the time?

It was not until I later read his biography that I was comforted to learn that “most of Professor Karski’s students probably knew little or nothing about his past. Story of a Secret State was out of print, he would not voluntarily bring up his wartime exploits, and even his faculty colleagues generally had only a dim knowledge of what he had done during the war.”

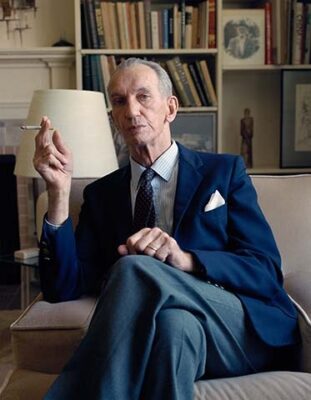

The Professor Karski I did meet in the fall of 1973 was still the “tall . . . man of striking appearance” noted by the Polish Ambassador to the U.S., Jan Ciechanowski, in 1943, whose “burning eyes reflected a keen intelligence.” He was still “too thin” as Martha Gellhorn (Hemingway) once observed when she interviewed him around the same time. He always did have “his omnipresent cigarette” in the words of his biographers (even in class—that was a different era after all). Add it all up, and Professor Karski was one intimidating presence. Even if I had known something of his background, I’m sure I would never have been able to bring myself to ask him about it.

Only now do I wish I could travel back in time and engage Professor Karski in person and learn what a truly inspiring human being he really was. And this is only the beginning of Karski’s remarkable story.

Karski as I remember him

[Coming in Part II: Karski sees Hell up close and personal; a meeting with President Roosevelt; years of triumph and tragedy.]